Kyoto Protocol: An Intriguing Multilateral Environmental Pact

Climate change is not a prognosis for the future, as some irresponsible governments believe. All countries are affected by and contribute to the cause of climate change. Some 150,000 human lives are lost each year as a result of climate change. One heat wave killed 20,000 people in Europe alone in 2003. More often invincible (!), the US is more vulnerable to natural disasters than terrorists attack. The successive floods in Bangladesh present the single biggest threat to the national security of such low-lying countries. Glaciologists have revealed that Himalayan glaciers, which feed major Asian rivers, will likely vanish within 100 years, leaving half of the world’s population in real trouble.

After nearly two years of dilly-dallying, the Russian Federation is set to ratify the most contested but only existing option — the Kyoto Protocol — to combat climate change. The go-ahead of Moscow’s decision marks the end of an agonizing wait for environmentalists and the most vulnerable low-lying countries worldwide. Still, the multilaterally agreed Protocol has yet to become a legal document, even after seven years of its inception. In all probability, the pact's fate won’t be clear before early next year.

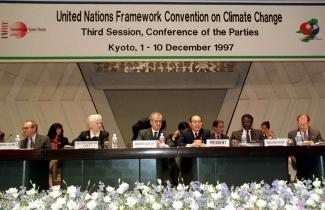

The Kyoto Protocol was signed at the third Conference of Parties (COP-3) to the UN-sponsored Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Japan 1997. The Protocol demands that 34 industrialized (Annex-I) countries, including the US, Japan, European Union (EU), Russian Federation and other OECD countries, should cut down 5.2 per cent (on average) of their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions below the 1990 levels in the period 2008-2012. Most significantly, the Protocol stipulates that 55 countries representing at least 55 per cent of all emissions must ratify the deal to make it legally binding. So far, 44.2 per cent of the emissions have been accounted for, although 124 countries have ratified the proposal. Russia accounts for 17.4 per cent of the total GHG emissions.

That is because the US, as the largest GHG emitter, with 35 per cent emissions, opted out of the Protocol in 2001. Questioning the fairness of the Protocol that excludes ‘major population center’ and ‘fast growing economies’ like China and India from this commitment, the US categorized the Protocol as ‘costly, ineffective, impractical and unrealistic’. In what could be termed as solidarity with the Bush administration, on October 30, 2003, the American Senate rejected Congress’ first attempt (this was also the first time climate change was debated in the Senate) to impose mandatory caps on GHG emissions in the US.

The “Delhi Declaration on Climate Change and Sustainable Development” adopted in COP-8 in Delhi 2002 says, “the parties that have ratified the Kyoto Protocol should strongly urge parties that have not already done so to ratify it on time”. However, during COP-9 in Milan in 2003, its relevance was questioned. Russia’s ‘now-yes and now-no’ hide-and-seek game has (also) jeopardized the fate of Protocol. President Putin’s cabinet decision is the repetition of the EU-Russia summit ‘compromise’ in May this year for Russia to enter into the World Trade Organization (WTO). As the Duma, the Lower House of the Russian Parliament, is primarily controlled by Putin’s United Russia Party, it should not be difficult to ratify the Protocol.

During the Delhi negotiations, a common theme appeared to be some of the rich nations trying to push the idea of developing countries committing to reduction targets. Throughout COP-8, developed countries kept up intense pressure on developing countries' commitments through repeated insinuations in speeches and statements.

The head of the Australian delegation said in COP-8, "What was needed was a 50-60 per cent reduction by the end of the century, and for this, all countries need to take action, including developing countries." A delegate from Denmark said, “Discussions on what will happen after 2012 have to start, and some developing countries need to start thinking of engaging in measures to mitigate GHG”. Developed countries could show leadership by meeting their commitments first. To begin with, they could ratify the protocol. Wasn't it ironic that countries such as Australia, which hadn't ratified the protocol, demanded developing countries to take on initial commitments?

Although there is a need to review for future commitment periods, the process should start with developed countries. The Year 2005 will launch fresh talks for the next round of commitments of (the period) post-2012. The year will also review the ‘demonstrative progress’ in achieving the commitments under the Protocol by the Annex-I countries. The coming 10th COP, which will be held in Argentina in the first week of December, will decide the future action on combating climate change. Due to its indispensability to the Kyoto Protocol, Russia should act now, or the Protocol will become a dead letter regime.