Maoist Resurgence in Chhattisgarh: Overhauling Counterinsurgency Strategy

There is an upsurge in Maoist related incidents in Chhattisgarh, a central Indian province. The violence on April 3, 2021, has raised a big question mark on the government's anti-Maoist strategy. Between 2018 and 2020, Chhattisgarh accounted for 45% of all Maoist related incidents in India and causing 70% of security personnel deaths (Ministry of Home Affairs, Annual Report 2019-2020)

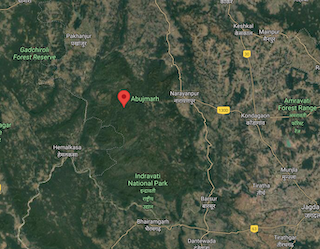

So far, the year 2021 has proved to be one the bloodiest years in terms of damages done upon the security forces by the Maoists. At the beginning of this year, five District Reserve Guard (DRG) soldiers were killed when Maoists blew up a bus carrying the DRG with an IED on March 23 in the Narayanpur district. Within less than ten days of that incident, the Maoists killed 22 security personnel while injuring more than 30 others on April 3, 2021. The Maoists also abducted one security personnel, who was released later. In addition, the Maoists killed one police assistant sub-inspector on April 23 after abducting him from Palnar village in the Bijapur district.

One unfortunate reality of the self-acclaimed anti-Maoist strategy in Chhattisgarh and also elsewhere in the country is that in the aftermath of all such incidents, immediately a fault-finding exercise starts, but in reality, no lessons are learnt from previous incidents. While the Bastar region of Chhattisgarh, a Maoist hub, was on the radar of K. Seetharamaiah, the founding father of the People's War since 1979, the government was clueless about the Maoist game plan for decades. However, even after the realisation, the government failed to act and preferred to only react. This is the main reason why Bastar is bleeding for so many years now.

The most notable anti-Naxal campaign in Chhattisgarh was Salwa Judum, which was launched in 2005 as a 'government-backed peoples resistance movement'. Salwa Judum means Peace March in the Gondi language, but in reality, it involved authorities directly arming tribals to take on the Maoists. Special Police Officers (SPOs) were drawn from among the Salwa Judum activists and were trained on the use of arms by the government. (India Today, July 06, 2011).

Salwa Judum drew flaks from several quarters, including the National Human Rights Commission. On the other hand, the Supreme Court too strongly pulled down the state for violating constitutional principle by arming youth who had passed the only fifth standard and conferring on them the powers of police. Finally, the Supreme Court, on July 5, 2011, asked the state of Chhattisgarh to disband the force of SPOs and Salwa Judum (The Hindu, July 5, 2011).

Operation Green Hunt, another anti-Naxal campaign (although there was never an official announcement for this with the nomenclature), was started in Chhattisgarh in the year 2009 along with Jharkhand Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. The operation, too, was heavily criticised for its dubious modus operandi. 'In a police operation with no clear name, timeline or goal, fought against a guerilla force that rarely wears uniforms, the Adivasis are learning that each side extracts a heavy price for supporting the other' (The Hindu, February 06, 2010).

Operation Green Hunt was replaced by an MHA scheme called SAMADHAN in 2017. It is an acronym where S stands for Smart Leadership, A for Aggressive Strategy, M for Motivation and Training, A for Actionable Intelligence, D for Dashboard-based Key Result Areas and Key Performance Indicators, H for Harnessing Technology, A for Action Plan for Each Theatre and N for No Access to Financing.

But the April 3 incident raised eyebrows regarding complacency on the part of the paramilitary forces and not adhering to the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). Of course, the security personnel tried their level best to follow the SOP, but what made them handicapped was the real-time intelligence. Instead of raising questions on SOP, it is pertinent to look into the Maoist drama of abduction of the SF personnel and his subsequent release after five days in captivity. Maoists took a leaf from the psychology of militancy and enacted the kidnapping drama, which was aimed to hard-hit the morale of the security forces. By releasing him, they wanted to recreate their heroic image among the masses and mislead the public. It is also important to examine how the release was secured. The jawan was released with the help of an eleven-member committee of mediators led by social worker Padmashree Dharampal Saini and two arbiters from the Maoist side.

If the Maoists wanted to send a message of reconciliation, then what made them abduct and kill the assistant sub-inspector on April 23? Murali Tati was abducted a day after Maoist commander Kosa Handa, who carried a reward of five lakh on his head, was killed in a counterinsurgency operation in Chhattisgarh's Dantewada. Handa had been an active Maoist for 15 years and was a Malkangiri area committee member and "military intelligence" in charge (Hindustan Times, April 24). Some media reports indicated that the body of the slain police officer was chopped off into many pieces. Here too, the Maoists' message was loud and clear -- they can be as ruthless as ever. In both cases, they wanted to convey that Maoist writ is stronger than any law or force in Bastar.

The COVID 19 pandemic has had its own impact on conflict dynamics across the world, including the Maoist conflict in India. The Chhattisgarh Police, on May 12, 2021, said that it suspects an outbreak of Covid-19 among Maoist ranks, citing a purported letter that mentioned an "illness" that many cadres had succumbed to (Indian Express, May 12). Subsequent reports also suggested that a few Covid positive Maoist cadres contacted a local policeman, who later helped to admit them at various hospitals for treatment. Given the fact that Maoist cadres live in the same locality where the local tribal population lives, the situation could become worse if appropriate measures are not taken soon. With almost nonexistent health care facility in the Maoist infested areas of Chhattisgarh, the threat looms large over the state to save the people who now face a new threat in the form of the spread of the deadly Coronavirus. This is a dire situation for the locals who are as it is already sandwiched in the ongoing battle between the security forces and the Maoists for long.

In a situation like this, it's difficult to have a full-proof strategy. But lessons need to be learnt in order to draw up a long term strategy to take control of the situation. Experiences from Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Jharkhand, and Maharashtra show that security forces achieve more success when the state police occupy the lead position. Chhattisgarh needs to drastically cut its reliance on Central Paramilitary forces and raise its own elite force. Surely, it has District Reserve Guard (DRG), but as a force, DRG needs more autonomy as well as expertise to take Maoists head-on. With the local police practically having no role in such type of operations, getting real-time intelligence is a big handicap that comes in the way of the security forces. Even as the capability of the Central Forces is doubtless, but unfortunately, they are forced to operate in the absence of local knowledge or intelligence. The harsh realities in Chhattisgarh call upon a complete overhaul of the existing counterinsurgency strategy that focuses heavily on a security-centric approach.

Second, the government must take a calculative risk to engage civil society in the process of conflict resolution. The experience gained from the Manhas abduction and release episode must not be put in cold storage. Similarly, the Tati episode of abduction and killing must come as a realisation that there should be no place for romanticism as the Maoist threat is more real than ever. Abduction as a Maoist strategy is not new, and it is observed that Maoists use abduction as a strategy once they are on the back foot. The crisis of leadership in the organisation sustained security offensives, and the Corona complications have undoubtedly put the Maoists on a back foot. In such a situation, it may be argued that the Union, as well as concerned State governments, must start thinking of holding talks with Maoist leaders during normal times instead of starting negotiations only after someone is taken, hostage. Civil society should also be involved in the exercise to check the growth of the Maoists and ensure the development of backward regions. In that context, the Communist Party of India (Maoist) needs to learn from the history of the world communist movement and work towards preparing the ground for a dialogue with the government.

Flexing the state muscles only through a security-centric approach has not yielded any significant results in Chhattisgarh. Government must wake up to the reality that human development and human security are inseparable. From the human development perspective, Chhattisgarh continues to portray the typical characteristics of a BIMAROU state (literally Sick) in certain parameters such as high poverty rate, high infant mortality and low life expectancy. The state needs to do a lot more to reduce the poverty rates, improve the literacy ratios, ensure employment, expand the network of health care, among others. Most importantly, the government in Chhattisgarh must tune up its anti- Maoist strategy in accordance with the classic formula of 'Clear, Hold and Develop'. It is high time that the government rose above the rhetoric and woke up to the harsh realities.