Environmental Threat beyond McMahon Line

The impending danger of bursting of an artificial lake/dam on the Pareechu River in the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China has been subsided. The Indian government, policymakers and security analysts were on tenterhooks till the danger was hovering over their head. The situation was in fact no less serious than the traditional military threat emanating from across the frontiers.

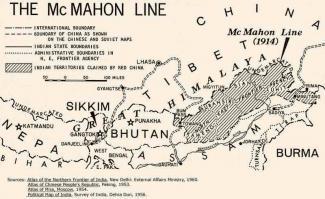

The impact of climate change in the Tibetan highland, the lifeblood of half of the World’s population, is no more a distant hypothesis. Geographically, India’s location makes it highly vulnerable to environmental threats originating from that region. The unstable reservoir formed due to landslide on Pareechu River, a tributary of the Sutlej River, during mid-July was, in fact, big enough to create havoc on the Indian side. This is one of the hundreds of ticking liquid bombs waiting to explode in coming years on both sides of the Himalayas.

According to one estimate of the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), there are 44 glacial lakes in Nepal and Bhutan, growing rapidly and would soon burst into a phenomenon called glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) due to climate change. Indian media had overlooked a similar incident when a small river Beki in Bhutan dammed and later burst to create havoc in Barpeta district of Assam during the Pareechu incident. The devastation in Himachal Pradesh in 2000 was attributed to GLOFs and not to the misperception of Chinese ‘weather weapon’. This time also media report indicated that the lake formed due to Chinese road construction or uranium mining in that area or a breach in the upstream, which the Chinese government has vehemently rejected.

The Himalayan ecological degradation is due to unmindful anthropogenic pressures in the form of unsustainable use of ecological resources for rapid urbanization and militarization of Himalayas. The Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had predicted that increased temperature and seasonal variability in precipitation are expected to result in the accelerated recession of glaciers and increased danger from GLOFs in the Himalayas. The IPCC had predicted in 2001 that there would be a ‘widespread increase in the risk of flooding for many human settlements’, especially in developing countries. The UN has also estimated that by 2025 over half of the people living in developing countries will be highly vulnerable to natural disasters. This prediction act as a precautionary approach to be followed by the governments. Unfortunately, awareness in Indian government establishment about GLOFs is non-existent, to say the least.

A Sino-Indian agreement regarding hydraulic information sharing on Brahmaputra River is in place since long. Although there is no such agreement to share information in this artificial lake case, China passed the first information to the Indian government. Contradictory information regarding the depth, length, width and magnitude of the reservoir created confusion and spread panic among the people of Himachal Pradesh, particularly those inhabiting alongside the 150 km of Sutlej River. Earlier, China did not allow the Indian technical team to visit the site citing various reasons. Even, many Indian defence analysts have questioned the Chinese transparency of passing the information regarding the lake. Why depend on the ‘unpredictable and unreliable’ neighbour, as Indian security analysts believe, for this type of information? Does India have its own intelligence establishment to track down such type of threats beyond its territorial boundary? Simple rhetorics won’t work in environmental threats as protecting the precious lives and property needs cooperation, consultation and information sharing.

This unusual incident indicates that if not monitored in time, the river systems may be a grave environmental threat. Real-time and quick information on natural disasters like these must be shared in border regions. In 2002, after much deliberation, India and China signed an MoU to help in forecasting floods caused by the Brahmaputra in northeastern India. The status of the Brahmaputra (Tsangpo in Tibet) is being received through e-mail twice a day. Way back in 1954 both the countries had signed a MoU to share hydrological data but unfortunately, the border war between the two in 1962 halted the progress.

Meanwhile, a six-member Indian delegation is invited by the Chinese government to visit Tibet and discuss various options to prevent recurrence of such a situation. India and China must agree to share information on river data and developmental projects to be taken or is on progress on all the rivers and streams that originate from Tibet. As a precautionary approach, they must discuss the lowering of water levels in the lakes, installation of state-of-the-art warning system or alert people living in the danger zone much ahead of time. As ecology comes under the Ministry of External Affairs and a member from MEA in the team to visit Tibet, one would expect that both countries need trust and comprehensive agreements to face the challenge of Himalayan ecological degradation.