Balfour Declaration and Making Palestine ‘Twice-Promised’

"Palestine was ‘twice-promised’ to Jews - first by the Bible and another by the Balfour Declaration".

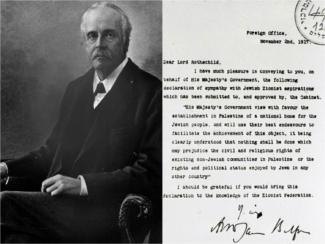

Anniversaries are moments of remembrance, and memories can be pleasant or painful. Balfour Declaration, a 67-word letter of support for Zionist demand for a Jewish homeland in Palestine from British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour on 2nd November 1917, which completes its hundred years this month, invokes both. For Israelis, it remains the first legal document legitimizing the state of Israel, while for the Palestinians, it represents dispossession and deprivation that continues to this very day. Anniversaries are also occasions to take stock of the things being remembered, their wider impact and how they influence the present.

Balfour declaration, like any legal document, had both its enabling and limiting clauses, and the controversy surrounding this document can be located within the matrix of these clauses. If the statement, ‘His majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for Jewish people’ was the enabling clause, then, ‘nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine’ was its limiting clause. Although these two clauses give a semblance of fairness to this document, it was an impossible task and balancing them resulted in a few grave tyrannies to one set of people in Palestine.

Three Tyrannies

That this declaration was tilted against the Palestinians can be discerned from the fact that it unproblematically came to accept the Zionist propaganda when Zionism emerged and confirmed Palestine as a site of its articulation of ‘land without people for people without land’. It was a notion popularized by eminent men like Mark Twain, who visited Palestine in 1867 and documented his impressions in his Innocent Abroad: ‘Palestine is a desolate country, whose soil is rich enough, but is given wholly to weeds- a silent, mournful expanse…. A desolation is here that not even imagination can grace with pomp of life and action’. Because of the unique agricultural practice of the peasants who came down to the plains for planting and harvest, their temporary quarters often appeared abandoned, creating an impression of Palestine among these visitors and Zionists far removed from reality. The Zionists, upon reaching Palestine, were in for a rude shock to find the place teeming with indigenous people.

Second, there was no way that the two clauses of the declaration could be balanced because in a place where the ‘non-Jewish communities’ comprised more than 90 per cent of the population, establishing a Jewish homeland without prejudicing their rights was indeed an impossible task. The real tyranny of the Declaration was not that it accepted one set of rights for one set of people, but lies in its complete denial of the similar rights to the Palestinian population in matters that dealt with their rights in their land.

This denial historically has imprisoned the Palestinians in what Rashid Khalidi, a leading Palestinian scholar, calls the ‘iron cage’. For him, the iron law of this conflict, from its inception in the early 20th century, has been a consistent refusal by the most powerful forces in this conflict- the Zionist movement (later the state of Israel) and its key supporters (Great Britain and the United States)- either to recognize or make room for Palestinians as a political community. The Balfour Declaration institutionalised this denial with such disdain that it lacked the necessary courtesy to use ‘Arab’ to refer to the overwhelming majority of people by simply describing them as ‘non-Jewish communities’.

Third, the post-World War I dispensation brought Palestine under British mandate wherein article 22 of the covenant of the League of Nations entrusted ‘the well-being and development of such people’- that is, of ‘peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world’, to the advanced nations ‘until such time as they are able to stand alone.’ Hence, the mandatory powers were merely to provide ‘administrative advice and assistance’ to people soon to be granted self-government in theory. This led to the third tyranny – one party was promising another a land that belonged to neither without the consent of the one who was its rightful owner!

British Fair Play

Balfour's declaration eventually calls the bluff of the British's oft-repeated claim for fair play because Jews were not the only party to which this land was promised. Similar assurances were also given to the Arabs in what has become famously known as the McMohan-Hussein correspondence of 1915. It was an exchange of a series of letters between the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali, and the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, also famous for the McMohan Line delineating Tibet from India, discussing the political status of Ottoman lands in West Asia.

The crux of the correspondence was the fate of Greater Syria, which, after having promised under Arab sovereignty, became the basis for the famous Arab revolt led by even more famous British colonel T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) against the Ottomans in 1916. Much of the acrimony between the two sides emerged due to the incompatibility of the two readings. While the British, by creating Transjordan (present-day Jordan) and giving it to Abdullah, one of the sons of Sharif Hussein, claimed to have fulfilled their pledge for the Arabs, the loss of Palestine strengthens a narrative that recounts the Arab story as one of betrayal and tragedy.

More bewildering was the third Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916. It was a secret agreement which envisaged a division that placed Lebanon and Syria under French control, Palestine, Jordan and Iraq under the British, while Russians would assume control of the Turkish Straits, a strategically important water body that connects the Aegean and Mediterranean seas to the Black Sea. It is important to note that while the post-war political map that emerged closely resembled the divisions envisaged in the secret deal, the only difference, however, was that the Russians had to miss the party because the Bolsheviks, instrumental in bringing the secret deal out in the public, had already dethroned the Romanov dynasty in 1917. All three agreements, taken together, take away the famed claim of the British sense of justice and fairness because they promised roughly the same territory to the two peoples with antithetical claims, while in the third, they secretly kept it for their own use.

If Britain committed a blunder, it would repeat the same mistake exactly a hundred years later by deciding to celebrate the anniversary with ‘pride’. Views like these prevent the healing of wounds that have festered for so long and make any sort of closure impossible.