Journey is the Reward: IAF in Transition toward Transformation

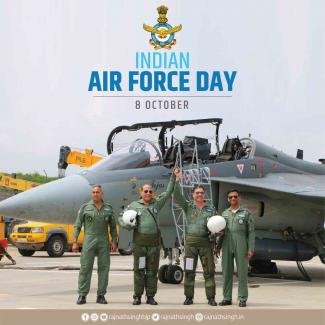

Indian Air Force (IAF) will celebrate its 91st anniversary on 8 October 2023. A proud day for all Indians, whether natural or naturalized or with roots in India yet settled abroad. As India celebrates IAF day and applauds a prominent of its military institutions devoted initially to protect territorial airspace and, in the process, getting recognition as a globally formidable aerospace power, it is a reflection time for all of us. Reflection is considered essential for the very simple reason that institutions evolve, and periodic reflections enable them to refine further into the future. IAF’s long journey may be summed up as what legendary Apple founder Steve Jobs told about his life: ‘journey is the reward’.

IAF’s journey precedes India’s independence in 1947. It was born on 8 October 1932, which was considered a subsidiary of the Royal Air Force (RAF), albeit evolving as an autonomous military institution with the name Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF) till 1950. Recognised for its immense contributions to allied forces during World War II, the RIAF still took a few years to be IAF as a structural transition from the British to Indian administration a few years took a few years after independence. Air Marshal Subroto Mukherjee became the first Indian to become Chief of the Indian Air Force only in April 1955. Coinciding with its evolution as an air power, complementing elements like military technologies as well as production efforts also evolved with time. DRDO’s predecessor, Defence Science Committee, started as a wing of the Chief of Army Staff to evolve into an autonomous branch, which continued as the flagship provider of military technologies. Hindustan Aeronautics Limited came after the government took control of privately held Walchand Hirachand, while Bharat Electronics Limited was also established in the 1950s. IAF’s quest for a supersonic fighter aircraft started with the HF-24 Marut programme in the mid-1950s, which lasted only till the late 1960s due to a variety of reasons like perceived inabilities of HAL, in sufficient scientific design and development back up from newly established Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE), lack of adequate politico-bureaucratic support and IAF’s trust deficit in indigenous production capabilities. India never learnt from mistakes, or rather harshly put, ‘India refused to learn from a noble failure. Orpheous aero-engine remained a dream.

Once MiG fighters started coming in, it bolstered IAF’s power for the next couple of decades. However, such was the arrangement with the Russians that neither Indian defence scientific nor industrial establishments benefited in any manner. The era of license production continued well into the late 1970s when India took a conscious decision to press for indigenous design and development of strategic systems like Main Battle Tanks, Naval systems like Submarines and Aircraft Carriers and frontline fighter aircraft (Tejas). The era of license production era still continued and flourished while indigenous programmes like Tejas languished. It took another military conflict in Kargil in 1999 when the country slowly woke up to reality and realized that ‘great powers invariably possess large indigenous arms industries’ and the gap between its stated aspirations to be a great power and its military, scientific and industrial prowess was too stark to go unnoticed.

India made a conscious decision to initiate and implement comprehensive reforms in its entire defence sector. Structurally institutionally, there were attempts to integrate and promote jointness among the armed forces. Although somewhat reluctant, the IAF pitched in to be an important part of new institutions like Tri-Service Command Strategic Forces Command and even created a rudimentary Aerospace Command within it. It realized and accepted the ground reality – a growing gap between rapidly evolving aerospace technologies and matching indigenous scientific and industrial power. As its growing demands for a rapidly depleting fighter fleet, as well as all other assets like surveillance, transport, combat and different versions of helicopters, continued to impact its modernization efforts, it has nevertheless shown remarkable agility, adaptability and combat effectiveness in recent times. Its role in surgical strikes across Line of Control in J&K or its standing tall in the ongoing standoff in the Himalayas against China.

Aerospace power and the role of IAF within the larger national military landscape have been very noticeable ever since the Modi government took over in 2014. Even with a temporary Defence Minister (late Arun Jaitley), the Modi government was decisive enough to approve major military acquisitions worth more than INR 70,000 crore, while former Defence Minister late Manohar Parrikar is credited with what may be called a ‘new era in military sector’, starting with the implementation of a series of reforms as recommended by the D B Sekhatkar Committee. India now has institutionalized the much-awaited position of Chief of Defence Staff, in which IAF appears well embedded. Much-pilloried aerospace product manufacturer HAL is now a listed entity whose market cap and bulging share prices say it all. HAL is not only over-flooded with orders worth more than INR 65,000 crore from IAF alone. It is expected to grab lucrative deals from countries like Malaysia, where it has already opened its overseas marketing office. IAF, on its part, after the multiple successes of ISRO and the emergence of local private satellite manufacturing companies, is well positioned to take its aerospace command efforts to an altogether new level. Structurally institutionally, it appears to embed itself into the new Indian military power complex.

IAF, however, can not afford to be complacent despite all such comprehensive yet sporadic successes. Its integration into the universe of national power must be complete – structurally and spiritually. Top IAF leadership must think hard about this aspect. IAF realizes that although it will have a sizeable Tejas fleet in current times and the future, its true indigenousness can only come when these are fitted with an indigenous aero-engine, not the GE-404 or GE-414. It is IAF’s responsibility to not only handhold HAL and ADE but also make sure that its reasonable expectations are met satisfactorily by these designing and production entities. IAF also knows that if current trends in the military-industrial sector are of any indication, as exemplified by an incoming competition between Mazagon Dock JV and L&T JV for the P-75 I naval project, HAL could also face competition from a Tata JV or an Adani JV in future fighter or other air asset contracts. IAF knows that all its aerospace assets – from aircraft to helicopters to unmanned systems to space assets – are technology-intensive, and capital guzzlers take a longer time to mature. Hence, its planners must draw up a practical yet affordable roadmap for its future directions. One thing that IAF has now is an unwavering political will, determined to take India into altogether new strata of the global power matrix.

With everything going well for IAF, despite challenges that are certainly not herculean by any standard, one can only wish IAF to make its wonderful journey more rewarding in future.

The article was originally published in Uday India Magazine, October 07, 2023.

Image Source: Twitter/Rajnath Singh (@rajnathsingh, Oct 08, 2020)