Space Bonhomie: China Launches Satellite For Pakistan

On May 30, 2024, China successfully deployed a communications satellite destined for Pakistan. The PakSat MM1, a versatile communication satellite, was launched atop a Long March 3 B rocket from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in Southwest China's Sichuan province. The satellite is positioned in a geosynchronous orbit and is slated to commence operations by August 2024.

The China Aerospace Science and Technology Corp (CASC), China's premier space contractor, has been entrusted with the PakSat MM1 project. This sophisticated satellite system was meticulously designed and constructed under its subsidiary, the China Academy of Space Technology, based in Beijing. With a liftoff weight of 5.4 metric tons, the spacecraft boasts nine antennas and 48 transponders spanning C, Ku, Ka, and L bands.

This state-of-the-art satellite, equipped with advanced communication technologies, is expected to diligently serve Pakistan's socio-economic agenda. It is engineered to offer a spectrum of services, including broadcasting, regional enhanced communications, and high-throughput broadband internet services. With an anticipated lifespan of 15 years, PakSat MM1 signifies a significant milestone in the collaboration between China and Pakistan in space technology. China's Great Wall Industry has provided these details, as has the international trade arm of CASC, which coordinated the satellite's launch.

Pakistan's space programme is under Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO), the national space agency. This agency was established in 1961 as a Committee and was granted the status of a Commission in 1981. This agency has been known to conduct research and development work in the field of space science and technology for many decades now; however, it has not been able to achieve much success towards expanding Pakistan's space programme.

Interestingly, Pakistan emerged as the third country in Asia to venture into the field of sounding rocket launches, following Japan and Israel. On June 7, 1962, Pakistan marked its inaugural foray with the launch of Rehbar1, a two-stage rocket. This pioneering mission saw the deployment of a sodium payload, propelling the rocket to an altitude of 130 km above the Earth's surface. Notably, this endeavour received support from the US space agency NASA.

During the launch, sodium vapour was released into the upper atmosphere. It was illuminated by sunlight refracted from below the horizon after sunset. This illumination facilitated the capture of photographs at various altitudes and locations. Analysis of these photographs helped assess temperature and wind directions in the upper atmosphere. The genesis of this project stemmed from NASA's requirement for upper atmospheric data over the Indian Ocean, which was relevant to their Apollo program.

In essence, Pakistan contributed to one of the most significant space programs in history. However, despite this promising beginning, Pakistan could not capitalize further on this opportunity.

The first satellite launched for Pakistan was Badr-1 on July 16 1990. The recent satellite PakSat MM1 is only the 10thsatellite launched by Pakistan in all these years. Some of these satellites are no longer operational. Today, Pakistan mainly depends on China to launch and build its satellites. However, Pakistan has made some progress toward developing indigenous satellites. One of the satellites launched by China in 2015, called PakTES-1A, was their indigenously developed scientific experiment satellite.

Recently, Pakistan embarked on an interesting mission in collaboration with China. As part of China's Chang'E6 lunar mission, Pakistan's ICUBE-Q satellite was carried along with it. On May 8, 2024, this satellite was deployed in the vicinity of the Moon. This ICUBE-Q satellite was meticulously designed and developed by the Institute of Space Technology (IST) and SUPARCO, Pakistan's national space agency, in collaboration with China's Shanghai University. This joint endeavour marks a significant milestone in Pakistan's space exploration journey and underscores the growing cooperation between Pakistan and China in the realm of space technology.

Pakistan's missile programme started around the mid-1980s, and it has short and medium-range missiles as well as cruise missiles in its arsenal. It is very surprising that Pakistan, despite being a nuclear weapon state, has not been able to build its own indigenous rocket launchers to put satellites into space. Today, it is the only nuclear weapon state with no space launch capacity. It may be noted that states the UK and France are part of the European Space Agency (ESA). Even a state like North Korea became spacefaring in 2012 and launched a few satellites.

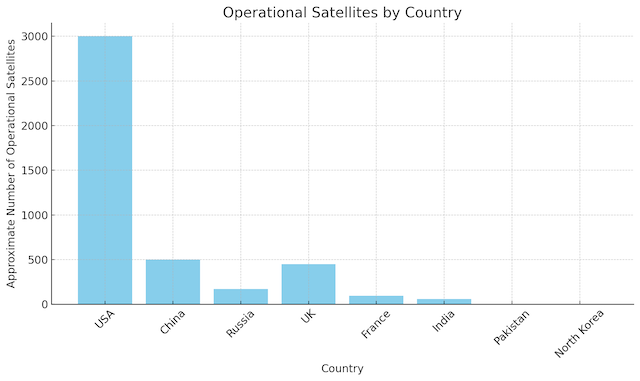

The following chart depicts the approximate number of operational satellites with nuclear weapon states. The United States leads the world in satellite operations, with approximately 3,000 operational satellites, reflecting its extensive investments in space technology for communications, navigation, and national security. China follows with around 500 satellites, highlighting its rapidly expanding space capabilities aimed at bolstering both civilian and military applications. Russia, with about 170 operational satellites, maintains a robust presence in space, focusing on defence, telecommunications, and scientific exploration. The United Kingdom, with approximately 450 satellites, plays a significant role in commercial and scientific satellite operations, whereas France operates around 95 satellites, contributing to European space efforts and maintaining capabilities in earth observation and telecommunications. India, with around 60 operational satellites, emphasizes space applications for development and security. Pakistan's space presence is modest, with 6 satellites, focusing primarily on remote sensing and communications. North Korea has a limited space presence, with only one known operational satellite, reflecting its nascent space capabilities.

For a nuclear-armed state, the deterrence architecture remains dynamic. Technological advancements necessitate continual upgrades to both nuclear weapons and delivery systems. Consequently, nuclear states must modernize their strategic nuclear deterrent. Presently, countries like India appear to be enhancing their nuclear triad capability. The nuclear triad comprises intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), and capable fighter aircraft/long-range heavy bombers. On March 11, 2024, India successfully tested a missile technology known as multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV) on the Agni-V ICBM. This test showcased India's ability to launch multiple (nuclear) warheads simultaneously, targeting various enemy locations. Meanwhile, reports suggest that Pakistan is augmenting its nuclear arsenal, albeit with no evident strides towards establishing a robust nuclear triad.

In the era of Network-Centric Warfare, satellite technology is crucial. All contemporary weapon delivery platforms rely on space infrastructure. However, Pakistan's limited investments in space hinder expanding its deterrence capabilities. Their modernization endeavours are severely restricted due to a lack of support from space technologies. A silver lining exists in China's support, providing military-grade space navigation signals (BeiDou). Furthermore, China may offer satellite-derived intelligence inputs when needed. While this support holds significant value in conventional warfare scenarios, the question arises: Is it in Pakistan's best interest to depend on China for its 'space' capabilities concerning nuclear deterrence?

Overall, it could be asserted that Pakistan maintains modest aspirations in space exploration. Recognizing their substantial lag behind key regional space players, they formulated their Space Vision 2040 over a decade ago. According to this vision, Pakistan aims to transition into a spacefaring nation by 2040. However, there seems to be a lack of a cohesive strategy to realize this ambition. Their goal includes sending an astronaut into space with China's collaboration. Analyzing Pakistan's historical and current trajectory in space exploration, it appears their reliance on China will likely persist for the foreseeable future.

References

“China delivers advanced communication satellite to Pakistan following successful launch”, Global Times, May 30, 2024. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202405/1313341.shtml

“China launches space experiment satellite”, Anhui News, December 30, 2022, http://english.anhuinews.com/newscenter/photonews/202212/t20221230_6590662.html

“China to help Pakistan launch miniature satellite in Chang'e 6 lunar mission”, Hindustan Times, October 01, 2023.https://www.hindustantimes.com/technology/china-to-help-pakistan-launch…

“How Many Satellites are in Space?” https://nanoavionics.com/blog/how-many-satellites-are-in-space/

“How Pakistan helped NASA in Apollo Program”, June 07, 2021, https://defence.pk/threads/how-pakistan-helped-nasa-in-apollo-program.713487/

Miqdad Mehdi, Jinyuan Su, “Pakistan Space Programme and International Cooperation: History and Prospects,” Space Policy, Vol.47, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2018.12.002.

“Pakistan Space & Upper Atmosphere Research Commission”, http://www.pakchem.net/2011/07/pakistan-space-upper-atmosphere.html